The UK Supreme Court has handed down its judgment in Iconix Luxembourg Holdings SARL v Dream Pairs Europe Inc and another, reversing the Court of Appeal’s decision and providing important guidance on the concept of post-sale confusion and the role it plays in trade mark infringement claims.

The Supreme Court has clarified two important questions concerning the assessment of similarity and likelihood of confusion in trade mark infringement cases. Its judgment will be of particular interest to brand owners in various sectors including white goods, sportswear, clothing and accessories, and those that face competition from lookalike products (including “dupe” products promoted by influencers).

Background

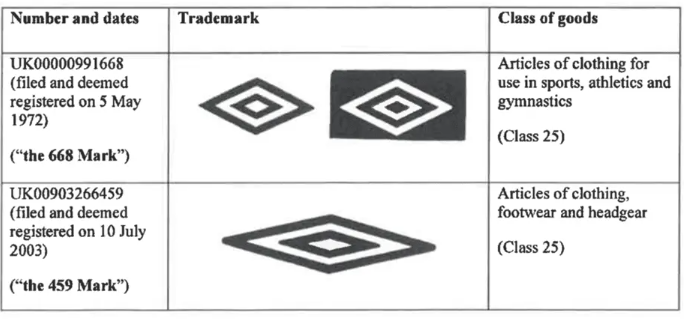

The case concerned two UK trade marks for the UMBRO double-diamond logo, registered for goods in class 25 and widely used on football boots. Iconix, the trade mark owner, alleged that Dream Pairs Europe Inc infringed the marks by the use of a similar logo (“the DP Sign”) on football boots, which were sold in the UK on platforms such as Amazon and eBay.

Courts take different views

Iconix brought the case in July 2021. It alleged that the DP Sign was similar to the UMBRO marks and that its use on footwear was likely to cause confusion on the part of the public under section 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, and also infringed under section 10(3). A notable feature of the case was that in the post-sale context the average consumer would encounter the DP Sign by seeing it from head height on footwear being worn by another person.

At first instance, the High Court found there was no infringement. The judge concluded that there was “at most a very low degree of similarity” between the UMBRO marks and the DP Sign, and there was no likelihood of confusion under section 10(2). He also found that there was no infringement under section 10(3), as there was no link between the DP Sign and the trade marks in the mind of the average consumer.

Iconix appealed and the Court of Appeal found in its favour. It concluded that the judge’s finding of a very low degree of similarity was irrational when considering the DP Sign affixed to footwear from any angle other than square-on. In particular, it found that when the DP boot was being worn and seen by an onlooker looking down, the DP Sign would be “foreshortened” and would look more like the double diamond mark. Conducting the multi-factorial assessment afresh, the Court of Appeal found there was a “moderately high level of similarity” between the mark and the DP Sign in the post-sale context and a likelihood of confusion.

In its judgment, published on 24 June, the Supreme Court unanimously allowed the appeal by Dream Pairs, saying:

“This was a case in which there were not matters such as irrationality, error of principle or of law which justified the Court of Appeal in substituting their own different view of the answer to the multifactorial question facing the judge from that which he had reached.”

It said the Court of Appeal was wrong to find that the first instance judge’s finding on similarity between the marks and the sign was irrational: "We would readily acknowledge that reasonable judicial views might differ on this issue about similarity when viewed from an angle, but our task is not to form our own view, unless both the judge and the Court of Appeal made what may loosely be called appealable errors."

The Court’s ruling is a victory for Dream Pairs as it confirms the first instance judge’s finding of no infringement. But the judgment also clarified two important issues in trade mark law.

Assessing similarity

First, the Court rejected the argument that extraneous circumstances, such as how the goods are marketed or subsequently perceived, are not to be taken into account in assessing similarity between the mark and the sign. Citing the CJEU decisions in Equivalenza and Audi AG v GQ, the Court gave five reasons why post-sale circumstances can be taken into account:

-

The CJEU judgment in Equivalenza is not authority for the proposition that, at the stage of assessing similarity, post-sale circumstances cannot be considered to establish similarities between the signs at issue.

-

Dream Pairs’ argument would mean that a global assessment of the likelihood of confusion would be ruled out in circumstances where there was no intrinsic similarity between the signs at issue even if, in a realistic and representative post-sale environment, there was similarity.

-

As long as the post-sale circumstances are restricted to those that are realistic and representative, the signs at issue would be found either similar or dissimilar.

-

The approach that at the stage of assessing similarity a court can take into account how the sign at issue is perceived in a realistic and representative post-sale environment is consistent with Equivalenza, where the CJEU stated that the "comparison must be based on the overall impression made by those signs on the relevant public".

-

Marketing conditions counteracting any similarity will be taken into account in the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion.

Role of post-sale confusion

The second issue concerned the role of post-sale confusion in the infringement analysis under section 10(2)(b). Dream Pairs argued that any post-sale confusion between the sign and the mark should only amount to actionable infringement if it involves confusion so as to affect or jeopardise the essential function of a trade mark as a guarantee of origin at the point of a subsequent sale or in a subsequent transactional context.

The Court rejected that argument, agreeing with the Court of Appeal that “it is possible in an appropriate case for use of a sign to give rise to a likelihood of confusion as a result of post-sale confusion even if there is no likelihood of confusion at the point of sale”. It gave six reasons for this finding. These included: none of the CJEU authorities supported the position advanced by Dream Pairs; there is no reason in principle for imposing such a limitation on the role of post-sale confusion; and Section 10(4) of the Act includes uses of a sign that are remote from the point when a purchase of goods or services or a transaction in relation to goods or services is concluded, such as advertising.

Key takeaways for trade mark owners

The judgment raises a number of interesting points, including:

-

Role of Court of Appeal: The Court’s judgment states that “the law has imposed structured constraints designed to prevent a free for all in a higher court whenever a party (with the necessary resources) wishes to challenge the first instance decision of the trial judge.” The Court of Appeal should only interfere in a decision if it identifies an error of law or principle; parties in trade mark cases should therefore treat the trial as the main event, not a dress rehearsal.

-

Relevance of EU case law: The Court made numerous references to the case law of the CJEU. Despite Brexit, this case law continues to be important for UK litigation and the Supreme Court has not diverged from it.

-

Post-sale factors: The Court stated that “realistic and representative” post-sale circumstances can be relevant when assessing similarity, and post-sale confusion can lead to a finding of likelihood of confusion (even in situations where there is no initial sale confusion). These findings will be welcomed by brand owners in sectors such as fashion and sports who have infringement cases against lookalike products. It remains to be seen what if any impact the judgment will have on trade mark oppositions and invalidation actions.

If you would like to discuss this case or the issues it raises further, please contact Carol Nyahasha or your usual contact at Kilburn & Strode.