BL O/643/19

Decision of UKIPO Hearing Officer lifts the lid on what the UKIPO considers an implicit disclosure.

Who is Akagi Nyugyo?

Relatively unknown outside Japan, Akagi Nyugyo is Japan’s biggest ice cream manufacturer with a staggering 400 million of its popsicles sold annually. Over the years they have been scooping up headlines for an eccentric corporate strategy, an appetite for taking risks (meat-flavoured ice cream anyone?), and a wide-mouthed gorilla-esque schoolboy mascot Gari-Gari Kun, who lends his name to the company’s most popular treat.

Gari-Gari Kun is a perfect example of Japan’s enthusiasm for mascot characters, known as Yuru-chara. Yuru-chara is the term for the cute and playful characters created to represent anything from a corporate organisation to an entire region. Some may have heard of Chiitan, a “0-year-old fairy baby” otter with no gender that wears a turtle as a hat, who was the unofficial ambassador of the small coastal city of Susaki.

And there is the annual Yuru-chara Grand Prix; with thousands of characters from across the Japanese archipelago attracting up to 50 million votes.

The company continues to innovate in the ice cream sector. A hearing at the UKIPO relates to an interesting new packaging idea which holds ice cream separately from sweets or a cold drink.

The “app-lick-ation”

The Examiner in charge of this application (GB1601247.8) believed that amendments sought by Akagi Nyugyo disclosed subject matter that was not present in the application as originally filed. The parties couldn’t resolve the issue and so a hearing was held.

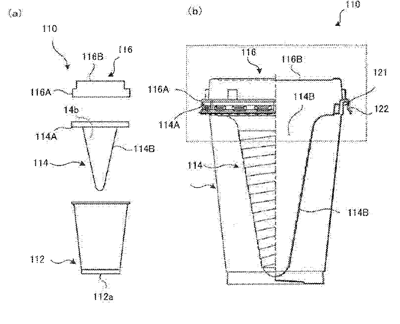

The specification described a “first example”, included for “background purposes”, and a very similar alternative arrangement known as a “first embodiment” (seen in the image). Both feature a cup-like body filled with ice cream, with an inverted cone known as the “inner lid” sitting inside it. Furthermore, an “outer lid” is fitted to the tops of the main cup and inner lid. A user must remove the outer lid to get to the sweets or cold drink inside the inner lid, which is then removed to get to the ice cream. The specification also stated that the outer lid of the first example could be substituted for a seal.

The key difference between the first example and the first embodiment is that the inner and outer lid are attached more tightly together in the first embodiment. This means the inner lid is more likely to be removed with the outer lid when the user pulls on the outer lid, rather than remaining in the main cup. The Examiner termed this the “different forces feature” of the first embodiment.

Proposed amendments

During Examination, Akagi Nyugyo had sought to amend one of the independent claims to include not just this “different forces feature” from the first embodiment, but also an alternative which could be derived from the “first example” of replacing the outer lid with a seal.

The Examiner’s arguments against the amendments

The Examiner objected to the inclusion of “a seal” in the independent claim as added subject matter by way of intermediate generalisation. The concept of intermediate generalisation was explained by Pumfrey J in Palmaz’s European Patents (UK) ([1999] RPC 47, upheld on appeal [2000] RPC 631), where he described that “the difficulty comes when it is sought to take features which are only disclosed in a particular context and which are not disclosed as having any inventive significance and introduce them into the claim deprived of that context. This process is sometimes called ‘intermediate generalisation.’” The Examiner believed that the amended claims combined two subclasses of the invention: one relating to the “first example” where a seal is used in place of the outer lid, and another relating to the “first embodiment” with the “different forces feature”.

The Examiner also referenced Nokia v IPCOM [2013] RPC 5 as a basis for it not being acceptable to introduce into a claim a feature taken from a specific embodiment unless the skilled person would understand that said feature is generally applicable to the claimed invention.

Attorney arguments

Akagi Nyugyo argued that the seal and “different forces feature” identified by the Examiner were not distinct, separate embodiments, but parts of a more general teaching. They claimed that a paragraph introduced the concept of a seal referring to all embodiments by contending that the Japanese character in the original PCT application referring to the outer lid of the “first embodiment” had multiple meanings, and could also be used to refer to a seal, cover, or sticker which forms the seal (similar to a yoghurt pot). This ambiguity, it was claimed, meant that a seal had been disclosed in relation to the “first embodiment” which also exhibited the “different forces feature”.

Conclusions of the Hearing Officer

Whilst disagreeing with Akagi Nyugyo that the seal had been explicitly disclosed by the Japanese character in the original PCT application, the Hearing Officer agreed that the paragraph referring to a seal with respect to the “first example” would plant the idea of a seal generally into the skilled person’s mind. In their view, “the skilled person would understand immediately from the context of the entire description that the frozen dessert needs to be satisfactorily contained so it does not leak out”, leading the skilled-person to perceive a degree of interplay between the “first example” and the “first embodiment”, helped by “closely-related reference numerals for common components (14 and 114, 16 and 116, etc.)”.

In light of this, the Hearing Officer accepted that the seal was implicitly disclosed in connection with the first embodiment, since the seal alternative was indeed generally applicable to the claimed invention, and thus was not susceptible of creating an intermediate generalisation when added to the claim. After addressing two potential clarity issues, the application was found to be in order for grant on the compliance date.

Analysis of outcome

When evaluating the robustness of the Hearing Officer’s decision, it is worth establishing what is generally admissible as an implicit disclosure according to the UKIPO Manual of Patent Practice (MOPP). The MOPP states in section 76.12 that “matter which is not disclosed, but which the skilled reader would find it obvious to add, is not regarded as having been implicitly disclosed”. With the Hearing Officer asserting that “the seal alternative was generally applicably the claimed invention”, a case could be made that the idea of a seal relating to the first embodiment might be obvious to add by the skilled reader but this may not be a ground for implicit disclosure.

Further, section 76.11 of the MOPP offers an example wherein the presence of a feature is not deemed as being implicitly disclosed due to it being “merely common but by no means universal.” It could be argued that the seal in relation to the first embodiment is not universal at all. For example, the skilled person may interpret “a seal” as being either a water-tight, air-tight or dust-tight barrier. With this in mind, a seal may not be necessary if sweets with a hardened sugar shell, e.g. M&M’s™, were held in the inner lid. The outer lid could have relatively large perforations, and would therefore not be a seal, whilst the sweets could remain inside the inner lid even if the packaging was held at various angles. Again, this section does not appear to provide justification that the seal was implicitly disclosed.

Section 76 of the MOPP was stated by Aldous J in reference to Flexible Direction Indicators Ltd’s Application [1994] RPC 207 as being “concerned with what is disclosed, not with that which the skilled reader might think could be substituted or what had been omitted”. Simply recognising that a seal could be substituted for the outer lid does not mean it was necessarily disclosed in the application. Alas, we are left no closer to the Hearing Officer’s conclusion.

Key take away

The Hearing Officer appears to have been particularly lenient with their interpretation of what may constitute an implicit disclosure. The practical patent advice from this case can be summarised as follows.

When drafting a patent application, ensure that it is clear and explicit which features described in relation to one embodiment can also be included in other embodiments.

If you would like to discuss this or other IP related matters with one of our attorneys, don’t hesitate to contact insights@kilburnstrode.com.