To commemorate Remembrance Day, Jim and I have written an article about what remembrance means to us and our military families.

Armistice Day, commonly known as Remembrance Day, is observed every year on and around 11 November to commemorate the day that the fighting ended in World War I. On this day, we remember all those who lost their lives in the two world wars and conflicts since. The National Service of Remembrance is traditionally held at the Cenotaph in London on Remembrance Sunday, alongside local services throughout the country, and many wear poppies produced by The Royal British Legion as a symbol of remembrance.

Emily Dyer

For me, Remembrance Day is an opportunity to reflect on stories of suffering, courage and sacrifice. Keeping these narratives alive is a duty that we owe to servicemen/servicewomen and their families.

I’d like to share some of anecdotes that I’ve been told while growing up. These stories highlight the extent of the effects of war – the servicemen/servicewomen who died on and outside of the battlefield, the intrusion of fear and loss into everyday lives, and the harrowing memories that continue to be present in the minds of many today.

WW2

My grandparents were young children during World War II, yet their memories are vivid.

On 10 February 1943, my grandfather (Tony) went to the cinema in his hometown of Reading. Tony was 4 ½ years old and since his dad was serving, he was often under the care of his grandparents during the day. His grandfather was commissionaire of the local cinema and so Tony had got a free ticket!

The Pathé News showed a tank and an aircraft approaching each other, ready to engage. The pilot dropped a bomb and Tony watched the animation of it rapidly falling, directly onto the tank. At the exact same moment as the explosion on the screen, young Tony heard a powerful blast and all the lights in the cinema shot on. Panic erupted and everyone ran outside. Out on the high street was complete devastation – if the bomb had fallen 400 yards closer, the youngster would have been directly in its path.

Four bombs were dropped in Reading that day, including one on top of the People’s Pantry, a popular restaurant, and a total of 41 people were killed. Perhaps most chilling is the recollection of witnesses that the pilot of the Dornier bomber smiled and waved as he flew away.

My grandfather still remembers every detail of this harrowing experience. You can listen to his interview with the International Bomber Command Centre here:

https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/10789

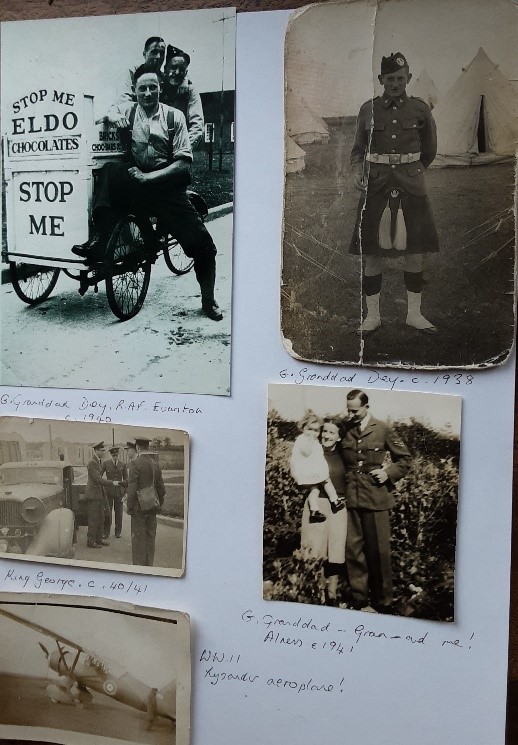

Tony’s father (pictured) served in the Corps of Royal Engineers and is believed to have been at Dunkirk.

My grandmother (Betty) also remembers a couple of scary experiences during World War II. One particularly memorable event occurred in ~1943 when Betty lived at Warren Farm, a hazard in line with runway 21 at Llandwrog, Wales. A pilot misjudged his landing and crashed into the roof of the farm! Luckily no one inside was injured, but all the crew except the pilot were tragically killed.

During World War II, Betty’s father was a drogue operator in Wales, training Polish airmen.

Conflicts in recent memory

My grandfather served for 22 years in the RAF as an Air Traffic Controller in the UK, Bahrain and Northern Ireland. Like many veterans, Tony doesn’t speak much of what he has seen. He is traumatised by his experiences and many of his fellow service men were killed or injured.

My grandmother also suffered while her husband was deployed. Left at home with two young children, she was largely reliant on the news for information of what her husband was experiencing. Though the RAF installed a telephone in the house for her to communicate with him, the phones where he was stationed were in high demand and so contact was scarce.

Stationed at RAF Scampton, Tony was a first-hand witness to the terror and anxiety of the Cold War. His job made this period even more terrifying for the rest of the family. My father, I’m sure like many of you reading this, recollects an intense feeling of fear and uncertainty during this time - he was never sure if he would see his father again when he left for work every day.

Tony recalls being in the ATC caravan at the end of the runway when the Vulcans scrambled - imagine the noise! The tension was broken one day by an amusing moment when a Vulcan came back from Cyprus with its bomb bays loaded with oranges!

Tony wearing his medals, including his British Empire Medal (BEM).

As an active member of The Royal British Legion, Tony continues his service to the British Armed Forces. He assists the organisation with their annual Poppy Appeal and other fundraising throughout the year. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, he also helped run a weekly coffee morning for ex-servicemen/servicewomen and regular music sessions at a local care home for residents suffering from dementia, many of whom were members of the forces and vividly remember their experiences of war.

Jim Miller

My father, two grandfathers and, in opposing armed forces, two great grandfathers fought in battle in the World Wars. For me, remembrance is about the duty that survivors and their families have to remember those who have been lost or hurt in war.

Let us cast our minds back to 2nd September, 1922 when this photo was taken.

Both of the newly married couple have been badly hurt by the First World War.

Hilda, my grandmother, a Kent Maid of fierce intelligence and dry sense of humour, did her war service in the local Post Office sorting room: the men ordinarily there had been sent away. The man in the photograph is the second that she has agreed to marry. The first was sent away and killed in the war, something she will think of almost every day for the next 75 years of her long life.

Born to Scots parents outside Kent and thus neither a Kent Man (from west of the River Medway) nor indeed a Man of Kent from east of the river, the man in the photo, my grandfather Lionel, has nevertheless fought with the White Horse Rampant of Kent rearing up above the county’s motto Invicta (i.e. undefeated, by the Conqueror) on his cap.

Lionel is an ordinary office worker like any of us at K&S but he has PTSD: for the 55 remaining years of his life after this photo was taken, he will dream nightmares about what he has done; the pain and shock of being wounded in battle; the terror of fighting hand to hand for life or death; those around him being killed; and his relentless carrying out of orders to kill as many as possible of the “enemy” (in fact, office workers, farmers and other ordinary people just like him).

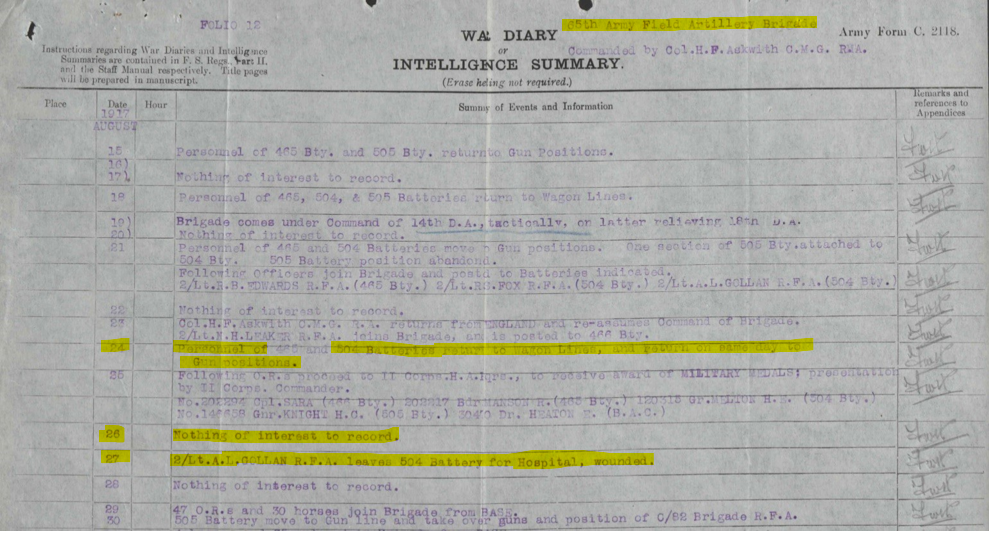

I doubt he dreams much of late 1918. Then, the War was becoming “easy”. His artillery brigade’s war diary – the daily log of where the brigade is, what it has done and which commissioned officers have been wounded, killed or are newly arrived – is remarkably chipper, filled with jolly entries such as “Excellent shooting match today!”, a severe contrast to the dour entries of 1914 and 1915 when the British were on the back foot.

So, he probably doesn’t dream much of 29th September 1918, Riqueval Bridge, possibly the most momentous battle that readers who have got this far have never heard about. It was the day that Lionel, with his six artillery guns, 60 men and 36 horses, took part in the largest artillery barrage ever inflicted by Great Britain. Just in front of him in the infantry were the elite yet untested New York “Silk Stockings” regiment with a unit of very tough battle-experienced Aussies set to charge in after them. The front line just ahead of them, defined by the St Quentin Canal, was the most heavily defended land in Europe and was the barrier between the two sides. As Lionel’s artillery barrage roared, the New Yorkers came up out of their trench and advanced through fog with the barrage rolling along slowly ahead of them to provide an elementary level of protection. But every one of the brave leaders of their running charge, the commissioned infantry officers among them, were soon shot down and the massive attack stalled: so, the veteran Australians were released from reserve, running forward through the now leaderless New Yorkers, the gritty Aussie NCOs, the corporals and sergeants, rallying the Americans forwards again.

By the evening, they had begun to cross the impossible obstacle – the canal is only quite narrow but has nearly vertical very tall embankments either side – and nearby to the right, a captain in the British West Midlands regiment had captured intact a small footbridge over the canal, Riqueval Bridge; the extent of allied troops surging through the undefended gap in the German “Hindenburg Line” here was such that the German Defence Staff informed the Kaiser that the war was inevitably to be lost.

The King visits Riqueval Bridge soon after it is taken

No, Lionel is more likely to dream of 6th December, 1915, a mining operation at Gallipoli when he was a trooper in the West Kent Yeomanry. In trench warfare, mining was a major activity: one would carefully dig a tunnel forward to underneath the other side’s trench, pack the area with explosives and then blow them up from underneath so there wouldn’t be much opposition when the men above charged forward to capture the trench. That was the idea anyway.

Except that the other side could have the same plan. On the 6th December, the West Kents’ mine tunnel dug straight into a similar one being dug by the Turkish defenders of Gallipoli. Hand to hand fighting underground! Not pleasant.

It’s hardly surprising therefore that, after Gallipoli, Lionel and many of the surviving Yeomanry, all expert horsemen, volunteered to transfer to the Royal Field Artillery, big guns pulled by horses: even though cavalry, which is what the Yeomanry were, could be told to fight underground, artillery could only be used above ground, so he knew he would stay above ground.

Riqueval Bridge in the 21st Century

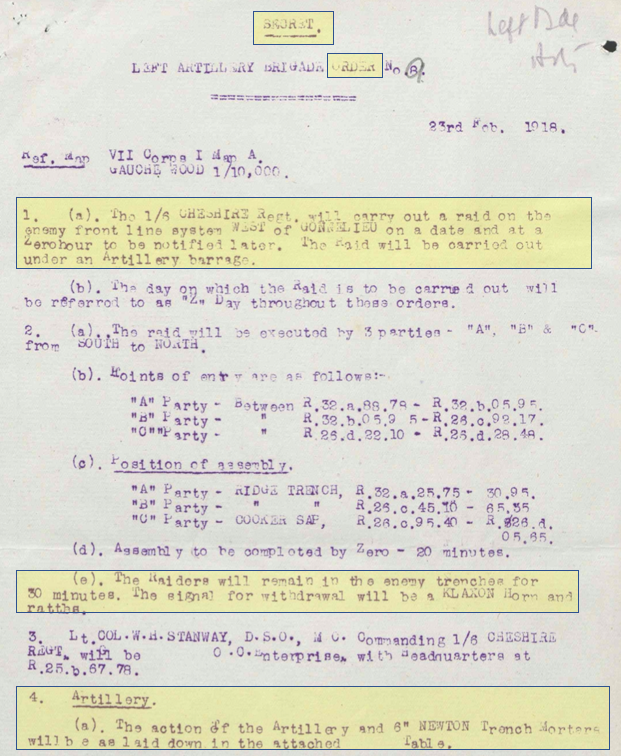

Lionel will also dream for the rest of his life of the countless times he has been ordered to kill as many people as possible, times like Gonnelieu in February 1918.

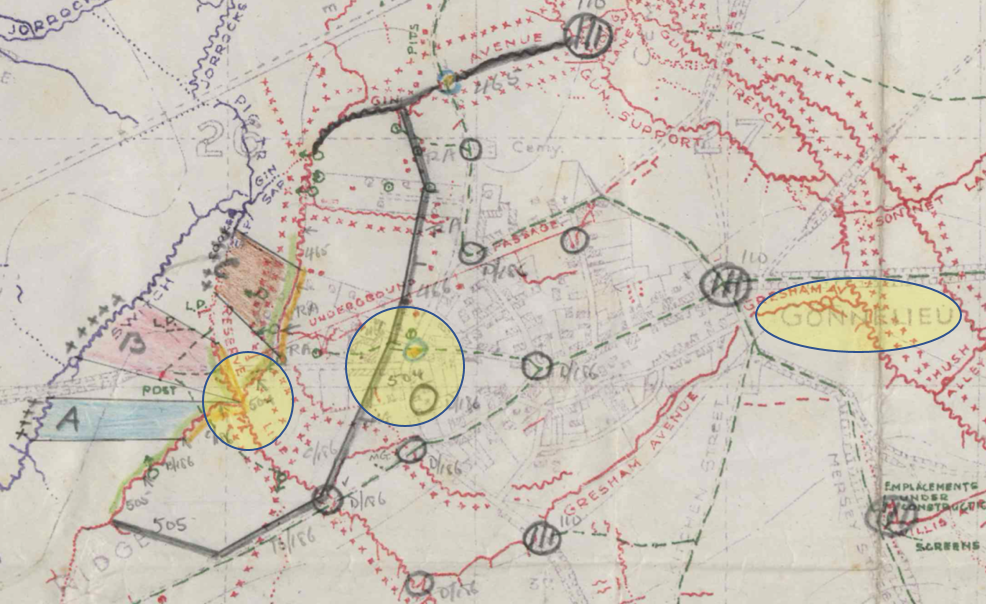

The orders issued to Lionel to hit the German trench and buildings at Gonnelieu

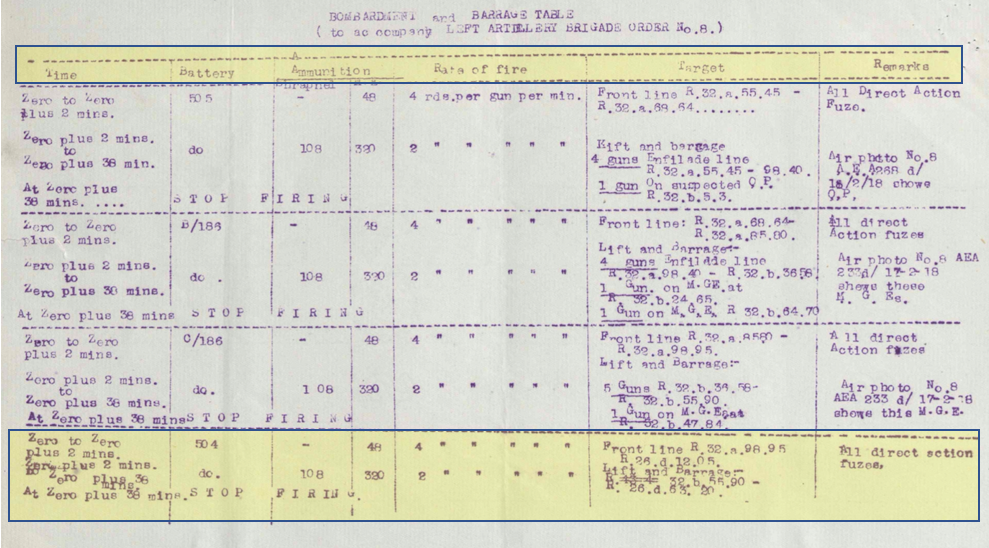

Lionel, with six 18-pounder guns in his No. 504 battery out of nearly 80 guns involved in the raid, is hereby ordered to support the Cheshire Regiment (the charging infantry.) He is ordered to fire 48 rounds at 4 rounds per gun per minute of direct action fuzed shells for the first 2 minutes, followed by 380 rounds at two rounds a minute.

Lionel's targets, essentially the locations of the men he has been ordered to kill, are marked “504” in pencil on his Brigade’s map of the German front line trench (red lines) accompanying the order. The Cheshires are to advance to it from the blue British front line trench, attack everyone inside it for half an hour, then withdraw back to the blue British front line trench. Lionel is to fire first onto the German front line trench, then to slow reinforcements by hitting buildings/roads further back.

But, most of all, Lionel is likely to dream of 26th August, 1917.

On that day, he set up his six 18-pounder guns in a beautiful corn field a few hundred metres square. The field is a few miles east of Ypres. The battle they were fighting was called the 3rd Battle of Ypres, or the Battle of Passchendaele after a small village some miles east.

The guns were well spaced apart. They were also well spaced back from the top of the field which forms a hill ridge: the smoke from the gun barrels would not reach the ridge so the position of the guns would not be betrayed as they fired. From the top edge of the field, Ypres was to the left, Hellfire Corner - a road junction targeted by the German artillery when British troops could be seen marching forward to the front line – was just to the town’s east. In front of and below the field was the low plain of the front line where hundreds of thousands of people were killed through the war. The infamous Inverness Wood and Polygon Wood, scenes of major blood baths, were clearly visible in the foreground to the right. A keen eye could spot Black Watch Corner, the site where in November 1914 a small Scots contingent from the Black Watch had held its line and defeated the attacking Prussian Guard, so preventing a breakout that would have seen Germany win the war there and then. Was that a good thing or a bad thing?

The corn field was an excellent place to site artillery. While every one of the many tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of men within range of Lionel’s guns, and indeed Lionel himself, could be killed by the other side’s artillery without warning at any moment, there was a certain freshness to fighting above ground, screened behind a hilltop. Except of course they weren’t hidden. There were these new things called aeroplanes. Aeroplane or not, for one reason or another, Lionel’s guns were seen on 26th August 1917 and accordingly were attacked by the German artillery. The attack was by shrapnel – shells which used a timer so as to explode in the air just before impact, like huge hand grenades which rained down many metal bullets. Lionel himself was hit by shrapnel, a small scrape he might call it in later life, yet it put him in hospital for 4 months. But he will dream on until the end of his life not only of the shock of being hit – and he went on to be wounded again in 1918 – but of one of his gunners who was killed that day in the corn field.

The loss of Lionel, a commissioned officer, to hospital is noted in the Brigade's diary. Even though he was in charge of one gun, as a Bombardier so the most junior rank, Alfred's death on the 26th is “covered” by “Nothing of interest to record”.

The date is now 26th August 2017, exactly one hundred years later.

Three middle-aged men, cousins to one another, are standing at the grave of a young man in a military graveyard at Zandvoorde, near Ypres, Belgium.

They are carrying out what they believe to be their duty to mark the centenary of the death of Bombardier Alfred Ashworth, 504th Battery, 65th Artillery Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. He was only 27 or perhaps 28 years old and was from Buxton, Derbyshire. He was a house joiner and skilled with horses, the latter necessary as each field gun was towed by 6 horses.

In the 504th Battery, Alfred had survived the Battle of Loos, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Pilkem and the Battle of Langemarck, but he was killed just days after the latter, a casualty of the Battle of Passchendaele. Back home, his father, five sisters and brother would learn of his death, but he never married and had no descendants. His tombstone has stood alone therefore for nearly a hundred years, though it and Alfred’s grave have been meticulously maintained by Belgian gardeners working with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

None of the three cousins has served in the military or the clergy. Yet all three stand ramrod straight as the head of the family, the eldest cousin Richard, a South African prop forward, holds a Bible in one hand and reads out the Royal Artillery Prayer from a sheet of paper held with the other. The middle cousin Tim, a West Midlands engineer, places a British Legion wreath on Alfred’s grave. The youngest cousin, Jim, is carrying a camera and a very old yet perfectly serviceable British artillery officer’s prismatic sighting compass.

The compass is marked “GOLLAN RFA”. It had been present when Alfred and Lionel were hit by artillery in the corn field exactly 100 years before.

Lionel, Belgium 1917 or France 1918. His cap badge bears the cannon of the British artillery’s Woolwich Arsenal, where the famous football team of the same name and with the same logo was founded.

A veteran of Passchendaele, the Second Le Cateau, St Quentin Canal and Riqueval Bridge, the prismatic artillery officer’s compass is the remaining tangible link between 1917 and 2017 and between Alfred and Lionel.

The three cousins are the grandsons of Alfred’s officer in command, Lieutenant Lionel Gollan, 504th Battery, 65th Artillery Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, formerly of the 1st Line, 1st Battalion, the Queen’s Own West Kent Yeomanry, who himself died after a good long innings 50 years ago.

The cousins are carrying out an act of remembrance. As Alfred had no children, they deem it their duty as grandsons of the officer in command on the day he was killed. There is nobody else to remember Alfred, an ordinary house joiner who, like Lionel an ordinary office worker and Hilda an ordinary young woman, was taken to places of horror, death and killing. Alfred and those like him should never be forgotten.

A wreath laid on Alfred’s grave at Zandvoorde, Belgium 100 years after his death by Jim’s elder brother Tim while the head of the family Richard, a tough South African prop forward and certainly no clergyman, read out the Royal Artillery Prayer: the three grandsons of the wounded officer honour the fallen comrade who has not been forgotten but remembered.

One of dozens of similar graveyards in the vicinity, the British War Ceremony, Zandvoorde, Belgium, 26th August 2017, with Alfred’s wreath showing up bright red in the centre. Alfred is still remembered.

AS used by Alfred and Lionel, Royal Field Artillery 18-pounder guns in action in 1918