The CJEU has delivered its judgment in Case C-17/24, CeramTec GmbH v Coorstek Bioceramics LLC, on 19 June 2025. This judgement follows AG Biondi’s Opinion of the case, which we recently discussed in detail in an earlier article, and confirms his position on the concept of "bad faith" in EU trade mark law.

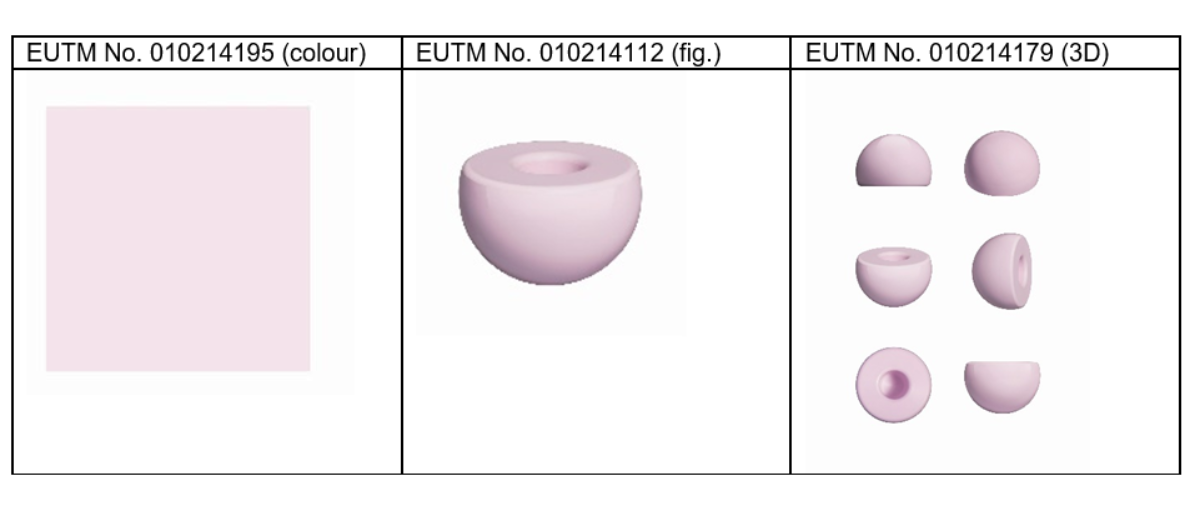

By means of quick recap, the marks subject to the dispute are:

Those marks were filed following the expiry of a patent (EP 0 542 815) in 2011, designating France and relating to a composite ceramic material (which, as you may have guessed, had the same nice pink colour).

We have discussed in our previous post that the (in)validity of a trade mark can be assessed through various lenses. In this case, the pertinent grounds for invalidity are:

-

Functionality: A sign cannot be registered if it consists exclusively of a shape or other characteristic which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

-

Bad Faith: An applicant is considered to have filed in bad faith if their intention is inconsistent with honest commercial practices.

By means of example, there have been parallel proceedings in the US, Germany and Switzerland. In the US, although the provisions are not exactly the same as in the EU, the CAFC has affirmed the cancellation of CeramTec's trade marks, finding the colour being applied to the marks to be functional (see Decision No. 23-1502 in CERAMTEC GMBH v. COORSTEK BIOCERAMICS LLC (Fed. Cir.)).

In France, however, the Paris Court of Appeal took a different approach and established that CeramTec had acted in bad faith, since it intended to extend its monopoly on the technical solution previously protected by its patent.

The referral for a preliminary ruling stems from from the French Cour de Cassation, following CeramTec’s appeal of the Paris Court decision. In simple terms, CeramTec argued that functionality could not characterise bad faith by itself. The Cour essentially asked:

-

Whether grounds of functionality are independent from and do not overlap with the ground of bad faith;

-

If not, whether bad faith can be assessed by reference solely to the grounds dealing with functionality, even if functionality has not been established; and

-

Whether that is so even if it later turned out that the sign (the pink colour) did not actually produce the technical effect previously believed.

The CJEU has ruled as follows:

-

1st question - Autonomy of Grounds for Invalidity: In line with the AG’s Opinion, the two grounds for invalidity (functionality and bad faith) are autonomous. This means that a trade mark can be invalidated for bad faith even if it is not found to be functional, and vice versa. The court can assess bad faith independently of any analysis of the sign's functionality. However, the grounds are not mutually exclusive.

-

2nd question - Assessing Bad Faith: The CJEU has slightly flipped this question around. The key is the applicant's subjective intention, which must be determined by reference to all relevant objective factors from that time. In line with the AG’s Opinion, the fact that an application is filed to protect a sign corresponding to an appearance that was previously protected by an expired patent does not automatically constitute bad faith. However, bad faith can be established by taking into account the functionality of the mark as one of the factors. Other factors (listed by both the CJEU and the AG) include the nature of the contested mark, the origin of the sign at issue and its use since its creation, the scope of the expired patent, the commercial rationale underlying the filing of the application for registration of the contested mark and the chronology of events characterising that filing. The CJEU also revisited the possible indicia of bad faith. In that regard, it recalled that even if a trade mark fulfils its origin function, it may nevertheless be declared invalid if it was applied for with the intention of undermining, in a manner inconsistent with honest practices, the interests of third parties.

-

3rd question - Belief at the Time of Filing: The decisive element is the applicant's intention at the time of filing. If the applicant believed that the sign produced a technical effect and filed the trademark application with the aim of extending its former patent monopoly and preventing competitors from using that technical solution, this can be considered bad faith. Crucially, the fact that it is later discovered that the sign does not actually produce the technical effect is irrelevant to the assessment of the applicant's bad faith at the time of filing. The AG essentially provided the same consideration in passing (even though he was asked not to answer this question).

Key takeaways

-

There is a strong motivation for businesses whose patent expires to seek other forms of IP protection, and trade marks can indeed provide enormous value (as they can last indefinitely, if valid and properly maintained). The healthcare industry is particularly well-suited for this “change of scope”, since consumers place important loyalty over features such as the name or get-up of the product previously protected by a patent.

-

However, this case serves as a useful cautionary tale in connection with less conventional marks such as 3D marks or colour marks. Whilst it will be for the French Court to reach a final decision, the CJEU’s Judgement (like the AG’s Opinion) does provide an indication that, subject to a more substantive assessment, bad faith can be established as regards these marks, when it is apparent that a party is seeking to extend a monopoly which should otherwise expire (i.e. a patent).

-

A crucial distinction must be made between patents and trade marks, and the purpose that they serve. These forms of IP can complement each other but should not overlap. Therefore, a trade mark that disguises and reflects the features of a patent will likely be invalid, whether it is because it protects features that are exclusively functional, or because it is indeed not registered with the aim of engaging fairly in competition.

-

This case is particularly interesting in that regard, as it also reflects how different jurisdictions are approaching the interplay between patents and trade marks.

If you have any questions relating to this topic, please get in touch with Carol Nyahasha, Fernando Di Blasi or your usual Kilburn & Strode advisor.