Every now and then, a patent attorney will come across an invention which seems too good to be true, for example, inventions which purport to ‘disprove’ or ‘violate’ various well-established theoretical laws of physics such as Newton’s laws of motion. These ‘impossible inventions’ are most closely associated with individual inventors who may not have the resources to experiment and prototype extensively before filing an associated patent application. In this article, we will visit three ‘impossible invention’ hearings at the UK IPO, before diving into some practical tips for those thinking of filing a patent application.

Case 1: Space craft fails to fly

At a UK IPO Hearing (BL O/065/21), the question of industrial applicability was considered by the Hearing Officer in relation to an invention of a system for propelling a space craft. Being ‘industrially applicable’ means that an invention must be able to be used in at least one kind of industry (i.e. that it can be made or works as claimed) and is a requirement for patentable inventions under Section 1 of the UK Patents Act.

Invention overview

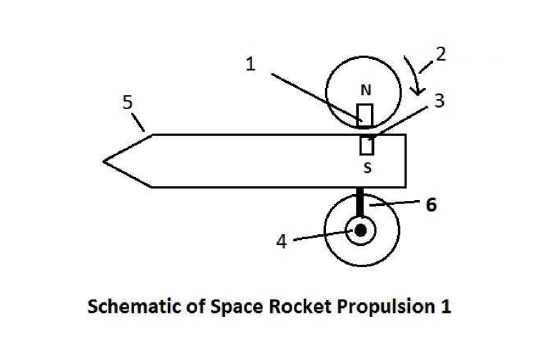

The invention was alleged to exert a force on the hull of a space craft by using a non-contacting magnetic coupling between a motor-driven wheel and the hull.

The above figure was included in the application. The space craft hull (5) has two wheels (6) each of which incorporates a magnet (1). The wheels are attached via spindles (6) to the hull which has a complementary magnet (3). A motor is used to cause the wheels (6) to rotate, causing the magnets on the wheels to apply a magnetic force to the hull (5)which allegedly imparts movement to the hull. The application claimed that as the magnetic coupling meant there was no direct mechanical contact between each wheel and the hull, there was no reaction force to the force applied by the magnetic wheel when used in space. This, in the eyes of the applicant, meant that the craft experienced no resistance to thrust and continuously accelerated whilst force was applied by the rotating wheel.

The applicant stated in their application that one of the difficulties of travelling in space is that there is no fabric, mechanism or substance to allow a reactionary force to operate and generate the action or propulsion force. They went on further to state that, in space, Newton’s third law of motion is not violated but delayed, missing or inoperable.

Industrial applicability

The Hearing Officer made reference to the UK IPO’s Manual of Patent Practice (MOPP) which outlines that processes or articles alleged to operate in a manner which is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws, such as perpetual motion machines, are regarded as not having industrial application.

The Hearing Officer asked the applicant a number of questions to see if it could be determined whether the invention worked or not. However, the Hearing Officer remained unconvinced by the applicant’s assertions that the invention would work, as Newton’s laws of motion apply equally in space as they do on earth. As such, being tethered to the hull of the space craft, no net force could be exerted by the wheels to stimulate motion.

Conclusion

The application failed to meet the requirement of industrial application because the principle of operation of the invention was contrary to well-established physical laws. Additionally, because the invention did not work, it also lacked sufficiency in that the specification of the patent did not disclose the invention clearly and completely enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the art. The application was therefore refused by the Hearing Officer.

Case 2: Laser-driven engine not on Hearing Officer’s wavelength

In another UK IPO Hearing (BL O/086/21), a UK patent application relating to a quantum laser-driven engine was refused. The invention was considered to contravene the laws of physics, leading to an irreparable double-act of industrial applicability and sufficiency objections, which often come hand-in-hand.

Invention overview

The application disclosed a method of generating thrust in an engine using a photon source arranged inside a chamber to fire photons at the internal walls of the chamber at different speeds. This, allegedly, would create an “internal direction pressure imbalance”, and thus thrust. Whilst the application’s description admitted that if the engine were used on the earth’s surface, friction or air resistance would dominate and the engine would not move, it asserted that in an environment with no resistance such as the vacuum of space, movement would occur.

Despite the applicant confidently asserting that “[the invention] disproves the law ‘every action has an equal and opposite reaction’, which is why it works”, the patent specification was held by the Hearing Officer to unsuccessfully disprove Newton’s third law of motion. The applicant’s arguments were also found to be unconvincing, having further failed to take account of the principle of conservation of momentum.

Conclusion

Consequently, it was held that the alleged invention did not generate thrust consistently with the laws of physics, so not only was it incapable of industrial application, but it could also not be successfully made by a skilled person reading the application. A fundamental principle of the patent system is that in exchange for the monopoly rights granted, the proprietor discloses enough information about the invention to teach the public how to carry it out – a requirement that a physically impossible invention cannot meet.

Case 3: Application for magnetic vehicle goes south

A GB patent application with the name of “Vehicle system based on magnetic repulsion” was filed in July 2016, with a request for substantive examination filed in January 2018. A hearing (BL O/100/21), was held in February 2021 after several rounds of amendment and examination reports, with sufficiency, novelty, and inventive step objections maintained throughout.

Invention overview

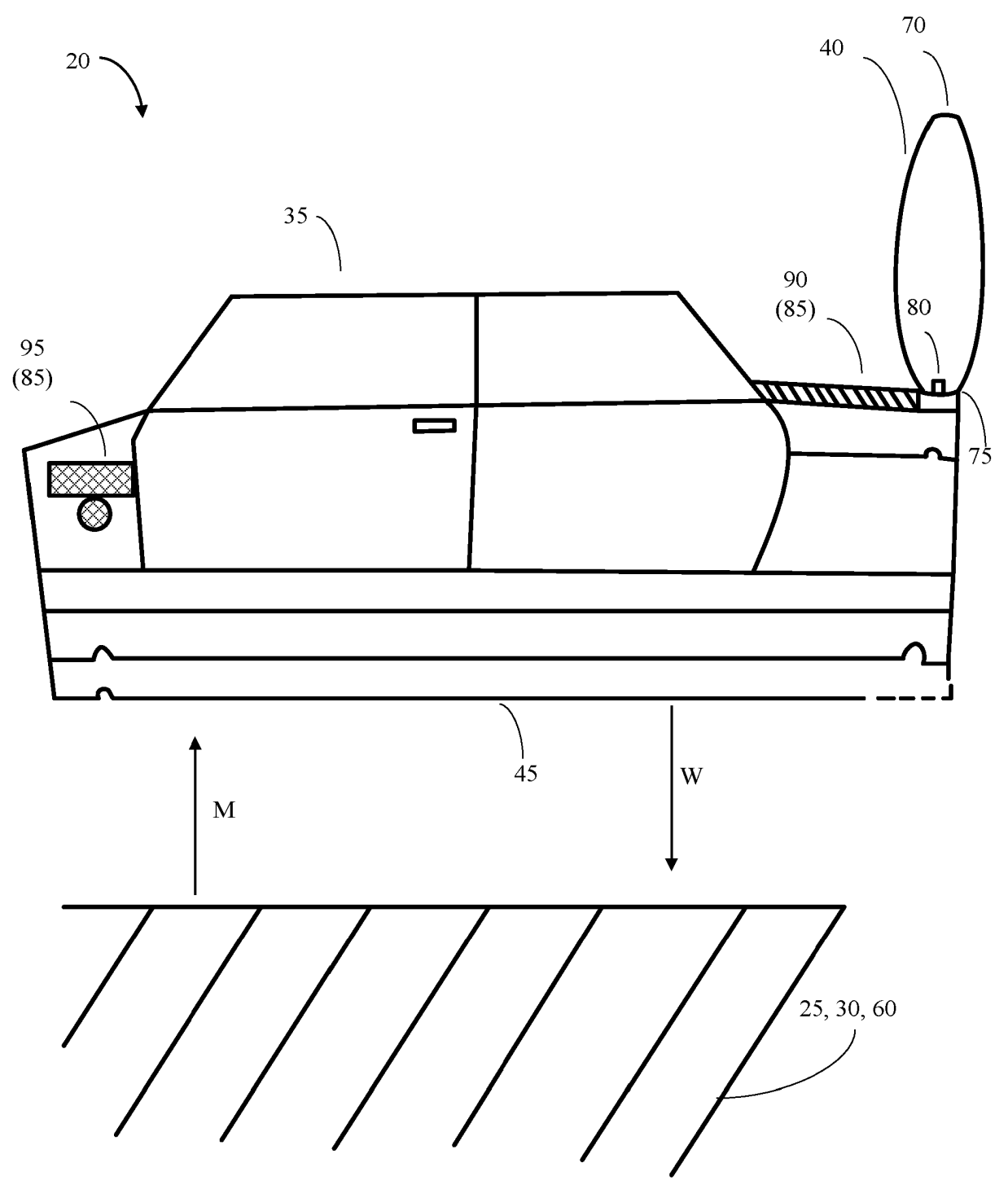

The application included two independent claims: one relating to a vehicle system, and another to a method of operating a vehicle. The vehicle was essentially a hovercraft with magnetic amplifiers attached, amplifying a magnetic field of a road surface with the same magnetic polarity as itself to generate the repulsive force necessary to hover.

Sufficiency

Without a clear and obvious violation of theoretical physical laws, the Hearing Officer took a slightly different tactic to the previous two cases outlined above. Before novelty and inventive step could be assessed, the Hearing Officer sought to determine whether the invention was sufficiently disclosed. In their view, it was unclear how the vehicle might amplify the road surface’s magnetic field as the application did not include any details relating to the construction or operation of the onboard magnetic amplifiers.

In order to assess sufficiency, the Hearing Officer got into the mind of the skilled person and considered both what kind of knowledge they might have, and what the specification would enable them to do.

Whilst conceding that the use of magnetic amplifiers was within the skilled person’s common general knowledge, the Hearing Officer could not find anything in the application nor prior art documents which demonstrated how a magnetic field emanating from a source separate to an amplifier could be amplified. All examples of amplification were ‘local’ magnetic fields amplified at their source.

Unfair disadvantage?

The applicant had argued that the extensive prototyping and experimentation which would be required to work out exactly how an amplifier might operate at a distance places independent inventors at an unfair disadvantage when compared with larger, well-resourced competitors. The Hearing Officer sympathised, but held that this line of reasoning was not relevant as an application must allow the skilled person to perform the invention without ‘undue effort’.

Conclusion

The Hearing Officer concluded that the application did not sufficiently disclose an invention such that a person skilled in the art would be enabled to perform it, and thus found it to be classically insufficient. Consequently, the application was refused.

Practical tips

So, what can we learn from these cases? Three things:

1. Enlist the help of a qualified patent attorney

Preparing, filing, and prosecuting a patent application can be a resource-intensive exercise, requiring the payment of various official fees and likely taking many careful hours of attention to put together. As UK and European Patent Attorneys are required to have high-level technical qualifications, they can help applicants to determine an invention’s feasibility and industrial applicability before significant time, effort and money is spent pursuing patent protection. They can ask questions to help identify aspects of the invention which may not work, as well as those which require more of an explanation to show that an invention works and is sufficiently described. Furthermore, Patent Attorneys can assist with determining the focus of the claims and avoid claiming an impossible effect.

2. Gather data or produce a working prototype to prove the invention works

Making a prototype and gathering experimental data can be valuable in evaluating whether the invention actually works. Data (from experiments with a physical prototype or computer simulations) can be useful to include in a patent application to prove that the invention works as described. The EPO’s Inventors’ handbook (link here) offers some useful, practical advice and information for inventors seeking to prove their invention. Make sure to take a look at its ‘prototype strategy’ subheading (link here) for insight on best practice for producing prototypes.

3. Make use of online resources

Your Patent Attorney can, of course, provide expert advice, but there are lots of online resources that are worth a look at before approaching a Patent Attorney. For example, the UK IPO’s Manual of Patent Practice (MOPP) provides some useful guidance on what types of invention are patentable. Section 4(1) of the MOPP (link here) includes examples, similar to those included in this article, of decisions made on British and European cases where inventions operated contrary to well-established physical laws. In addition to utilising the MOPP, a simple patent search using the European Patent Office’s patent searching service Espacenet (link here) can help to identify relevant prior art documents.

Further reading:

For more information on industrial applicability and its relevance to perpetual motion machines and sufficiency, our very own Kathryn Sayer and Josh Green have written this enlightening article here containing useful and practical tips for attorneys and inventors alike.

If you would like to contact Robin or Josh, feel free to reach out via email or social media:

Twitter

LinkedIn