Industrial applicability and why it matters

Industrial applicability, alongside novelty and inventive step, is one of the conditions an invention must meet in order to be considered patentable at the EPO and the UK IPO. In the real world, this means if an invention cannot be used in at least one kind of industry, it is not “industrially applicable” and therefore cannot be patented. However, most inventions are not challenged in this regard. The EPO’s Guidelines for Examination state: "In most cases, the way in which the invention can be exploited in industry will be self-evident, so that no more explicit description on this point will be required”1. A similar requirement exists under US patent law, in which an invention must have “utility” in order to be considered patentable2.

An objection to a lack of industrial applicability may not be one which patent applicants and patent attorneys experience on a day-to-day basis. However, it is certainly not a requirement which should be overlooked. It is especially important to consider, where the subject-matter of an invention may seemingly err on disputing the boundaries of the laws of physics.

One class of invention infamously considered not capable of industrial application, and therefore not patentable at the EPO3 or the UK IPO4, is the perpetual motion machine (PMM). Here, we’re going to look at some of the challenges faced in trying to patent PMM inventions, and we’ll give our tips on how the lessons we can learn from these challenges can be applied to seeking patent protection for other inventions too.

What is a perpetual motion machine and why are they considered non-industrially applicable?

A perpetual motion machine is, in theory, a machine that never stops and requires zero external energy input to keep running. There are generally considered to be two types of PMMs; the first being those which can sustain themselves and the second being those which can actually output energy. In today’s energy crisis, this second type is an appealing concept. Some inventors have been fascinated by the idea of building a PMM, with one of the earliest recorded such ideas being known as the ‘overbalanced wheel’ concept (shown below) believed to have been developed in the 12th century by Indian mathematician Bhāskara II5 – a wheel which takes advantage of a force imbalance during rotation, caused by the irregular spacings of the arms.

Figure 1: an overbalanced wheel

The very concept of PMMs contravenes the laws of physics by violating either the first and/or second laws of thermodynamics. These laws state that energy cannot be created or destroyed (the first law) and that entropy in a closed system must increase with time (the second law) i.e. as processes occur, energy is lost through inefficiencies such as friction and heat loss. In the case of the overbalanced wheel, even though there may be moments where the forces on the wheel itself are in fact balanced, friction between the wheel and the axis on which the wheel sits prevents the perpetual motion of the wheel, such that it will eventually stop.

It’s therefore clear that the overbalanced wheel does not disprove the first and second laws of thermodynamics i.e. as the wheel spins, energy is lost through friction and the machine will eventually stop without an external energy input. However, there have now been multiple cases of inventors managing to design overbalanced wheels which will run for long periods of time. Although these periods of time are by no means ‘perpetual’ (i.e. they do end eventually), this raises the interesting question of how long is long enough to satisfy a patent office that an invention will run forever (i.e. is perpetual)? If a patent office receives an application for a PMM (bearing in mind that there is no requirement that a working model of an invention be submitted), the only criteria on which the patent office have to examine the application are the theoretical laws of science. As such, the EPO and UK IPO (and most other patent offices around the world) view applications relating to PMMs as unpatentable for the simple fact that if the invention is theoretically impossible, it cannot be industrially applicable3,4.

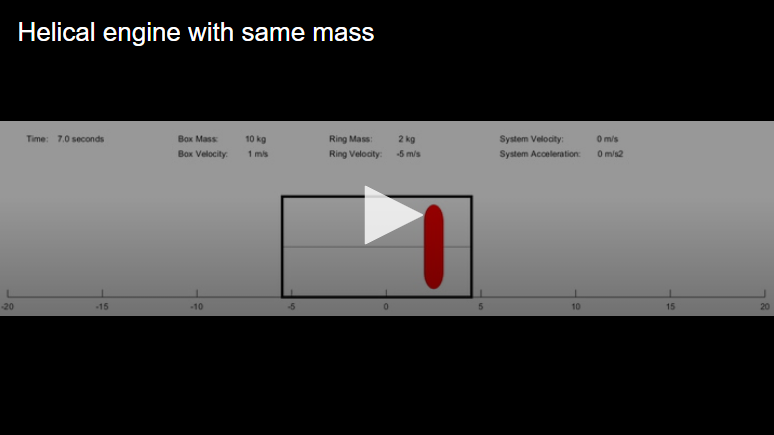

However, the patent system is designed to promote continuous innovation and it is therefore important to continuously evaluate what is theoretically and practically possible. For example, NASA engineer David Burns has recently designed a “helical engine” which he believes could propel aircraft without the use of a fuel source5. The idea makes use of the fact that every action has an equal and opposite reaction (Newton’s third law of motion), but also requires that, with no external input, an object’s mass is changed (a fact that we currently allow for as particles are accelerated to the speed of light in particle accelerators). Through this change in mass, a second object can be made to accelerate. This idea is illustrated in Figure 2 below, where the particle gains mass when moving in the forward direction and loses mass when travelling in the backward direction. This means that as the particle is travelling in the forward direction, its collision with the container has more impact than the collision occurring when the particle is travelling in the backward direction, resulting in a net movement in the forward direction.

Figure 2 – visual representation of a particle causing a container to accelerate with no external energy input

Although Burns’ idea is believed by some to be theoretically possible, the technology needed to test such an idea (which would only ever be possible in the friction-free environment of space) is still a long way off, making it currently practically impossible, at least here on Earth.

Relationship with sufficiency

In exchange for the monopoly rights given to a patent proprietor, a patent application is required to sufficiently disclose to the public how to carry out the claimed invention i.e. to give enough information about the invention so that a person reading the patent application would be able to make or perform what is described.

One parallel between industrial applicability and sufficiency is that both a failure to satisfy the requirements of sufficiency of disclosure, and a failure to satisfy the requirements of industrial applicability can be irreparable. That is, an applicant may not be able to amend their patent application to rectify such an issue, meaning that the chances of obtaining a granted patent could be ruined. This is in part due to the fact that at the EPO and the UK IPO, there are strict requirements for amending a patent application, and it is generally not permissible to add subject-matter which was not disclosed in the original filing.

For example, the successful performance of an invention such as a PMM would be inherently impossible due to its lack of compliance with the laws of physics. A patent application to such an invention would therefore lack sufficiency of disclosure, because a member of the public reading the application would not be able to successfully carry out the invention. For the same reason, it would also lack industrial applicability4,6.

In practice, an objection to a lack of sufficiency of disclosure might be raised instead of, or in addition to, one to industrial applicability. The two requirements are often intertwined in cases concerning PMMs. For example, in Peter Crowley v Comptroller General of Patent7, Mr Crowley’s UK patent application (no. 0819309.6) was refused on both of these grounds. The supposed invention was a machine alleged to generate an energy surplus without an energy input. The machine was considered to go against the first law of thermodynamics, as the hearing officer considered that the machine would eventually slow down and come to a halt due to friction and turbulence. In legal terms, this means that the machine was not capable of industrial applicability. The patent application was also found to be an insufficient disclosure as it would be impossible for a member of the public to produce such a machine, since it contradicted the first law of thermodynamics.

Practical tips

The requirement for industrial applicability and its relationship with sufficiency raises important considerations regarding timing and filing strategy when pursuing patent protection (not just for PMMs, but for other inventions too), such as: when should a patent application be filed to fully exploit an invention's worth; and, can a patent application be sufficient if no working version of the invention exists yet?

-

Consider the timing and content of your application

The date of filing and what to include in a patent application should be carefully considered. Although most patent offices now work on a “first-to-file” system, this does not necessarily mean that filing at the earliest given opportunity will always be beneficial.

If an invention hasn't yet been developed through to the stage where it has been proven to work, filing an application could risk an objection to a lack of sufficiency and/or industrial applicability being raised. Such an objection may be irreparable and result in patent protection being denied for the invention. A careful balance should always be sought between filing as early as possible and making sure that the invention is both industrially applicable and sufficiently described.

-

Gather as much data as possible

Where a working prototype of a product implementing an invention has not yet been made, it may be prudent to wait until specific details concerning the workings of the invention have been determined and can be included in the patent application. It might even be worth gathering data to prove that the invention works. In some cases, it may be more appropriate to rely on trade secrets to protect the intellectual property of such an invention in its infancy (though this might not be appropriate for inventions which can be easily reverse-engineered).

-

One vs several applications

Another option for protecting an invention in its infancy may be to file several separate patent applications each directed towards a different improvement or element of the overall invention. Such a strategy may though be best suited to more mechanical-type inventions. Some proprietors may see this as a way to get around the requirement for industrial applicability, in the case of trying to protect a PMM, for example. Although a larger invention constituting several component parts may be found to have no industrial application, the components themselves may be readily applicable elsewhere and, therefore, may be individually patentable. By employing such a strategy, patentees may be able to gain protection for inventions which would otherwise be refused for lacking industrial applicability.

-

Commercialisation

An understanding of the most opportune moment to file a patent application can be best gleaned from an understanding of the current commercial and technological landscape. It is important to remember that first and foremost, a patent is a commercial tool, and it is important when considering filing an application that an actual benefit can be derived from obtaining a monopoly right to the invention. This monopoly can last up to 20 years from the filing date of the application, provided the actions necessary to keep the patent in force are completed. If a patent application is filed before the necessary infrastructure to work the invention is available, there is likely to be no need for the invention, and the opportunity to exploit the rights conferred by the patent application may be severely limited.

As the global interest in the space industry continues to grow, it will be interesting to see how, or indeed if, NASA pursues Burns’ “helical engine”, and what approach they take to protect it. If a working prototype employing Burns’ concept is successfully developed and tested here on Earth, or in space, perhaps we could begin to see a new emergence of patents being granted for PMM inventions. Let’s watch this space…

If you would ever like to have a word with Josh or Katy about the content of this article, don’t hesitate to contact them via email or contact your regular Kilburn & Strode advisor.

1 https://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/guidelines/e/f_ii_4_9.htm

2 https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2104.html

3 https://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/guidelines/e/g_iii_1.htm

4 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/manual-of-patent-practice-mopp/section-4-industrial-application

https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2018/12/03/six_perpetual_motion_machines_and_why_none_of_them_work.html

5 https://www.newscientist.com/article/2218685-nasa-engineers-helical-engine-may-violate-the-laws-of-physics/

6 https://www.epo.org/law-practice/legal-texts/html/guidelines/e/f_iii_3.htm

7 https://www.ipo.gov.uk/p-challenge-decision-results/o38913.pdf