“The well-known elephant test. It is difficult to describe, but you know it when you see it.”

(Lord Justice Stuart-Smith, on land law, Cadogan v Morris [1998] EWCA Civ 1671)

When drafting patents for mechanical inventions, insufficiency issues are rare. The majority of insufficiency case law relates to chemical inventions, however, there are still some nasty traps that one can fall into accidentally. In this article, we look at a few examples and discuss potential issues when filing patent applications directed to mechanical products and processes.

Background

The basic principle behind the patent process is that in return for informing the public how to recreate an invention, the applicant is entitled to a 20-year monopoly for the invention. In the application the disclosure of the invention must be sufficiently clear and complete to enable a skilled person to carry out the invention. If it is not, then the application may be rejected by the Patent Office or could be open to attack during opposition or revocation proceedings.

In both Europe and the UK, there are three main types of insufficiency to look out for:

-

Classical insufficiency (missing information/ not enabling)

-

Insufficiency by excessive claim breadth

-

Insufficiency by ambiguity

Insufficiency by excessive claim breadth can occur when the claim encompasses inventions which are not fully described in the application. A disclosure of one way of performing the invention is sufficient only if it enables performance across the whole of the claimed range (T 409/91).

If the claims are so ambiguous that it is not clear how to recreate the invention, then this can also lead to the patent being rejected for insufficiency. This can often occur when test parameters are included in the claims. As Mr Justice Birss said: “If the skilled person cannot know whether they are carrying out the right test, then the claim is truly ambiguous and therefore insufficient.” (Mr Justice Birss, Unwired Planet International Limited v Huawei Technologies et al. [2016] EWHC 576 (Pat))

Insufficiency can be likened to the “elephant test” mentioned by Lord Justice Smith (above). This is because “The elephant is characterised more by recognition when encountered than by definition” (Lord Hughes, on dishonesty, Ivey v Genting [2017] UKSC 67). You will recognise it, IF you see it.

The challenge for the IP manager or attorney team when drafting and approving a patent for filing is to spot this elephant, bearing in mind that insufficiency can be hiding in plain sight.

What to look out for

It is important for the person drafting the application to thoroughly understand the invention and the scientific principles behind it. Frequently, when mechanical cases are rejected for insufficiency, it is because the claims appear to contravene one of the laws of physics (such as Newton’s Laws of Motion) or because the Patent Examiner does not believe that the invention would operate in the manner described.

Missing information can also lead to a rejection for insufficiency, particularly when the description does not provide details of the features of the claims (see O/042/21, for example), or contradicts the claims. When claims mention a feature as if it is common general knowledge, but this feature is not widely known, and not described in the application, then the application could be insufficient (see O/100/21, for example).

All too often, an insufficiency objection is raised because of measurements or test parameters that have been included in the claims, but which are not well defined in the description. Any claimed measurements have to be reproducible under exactly the same conditions. Details of all the measuring parameters and equipment should be provided.

Sometimes it can be hard to spot the elephant at first. This is illustrated by the following examples. All but one of these applications made it through the examination stage and progressed to grant, but when challenged by third parties, the patents were revoked (or amended) because of insufficiency issues.

Examples

(a) Classical Insufficiency & Missing Information

Classical insufficiency includes situations where the information that has been provided doesn’t enable the skilled person to actually make the claimed invention.

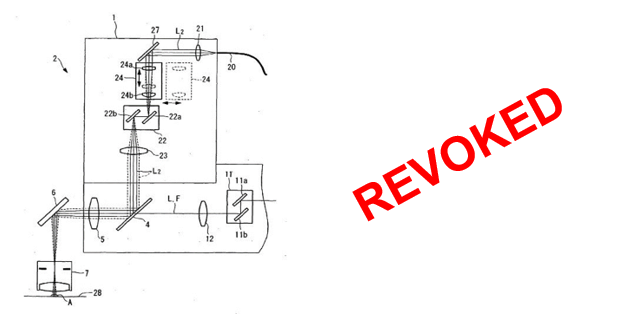

In this example, an accidental omission in the description led to an insufficiency objection. EP1857853 (filed by Olympus Corporation) relates to an illuminating device. Claim 1 included the phrase: “… at least one lens (24a/b) configured to change the numerical aperture of the illumination light at the pupil plane (7a) of the objective lens …”.

The figure appears to suggest that lens 24a can be moved in the direction of the arrows towards 24b. The application did not provide details of any configurations which might be used to change the numerical aperture.

The patent application was revoked during opposition proceedings brought by Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, and then this decision was appealed.

Upon considering this case, the Appeal Board reached the opinion that the application is insufficient, concluding that “...moving a lens along the optical axis generally displaces the position of the point where the light focuses. It is not clear from the patent, how the lens 24a of claim 1 is to be configured in order to change the numerical aperture without moving the focusing point of the system in the pupil plane of the objective lens and without moving the second lens 24b of the illumination area adjustment unit 24.” The appeal was dismissed.

It was unfortunate for Olympus that a relatively small omission from the description led to the loss of the patent.

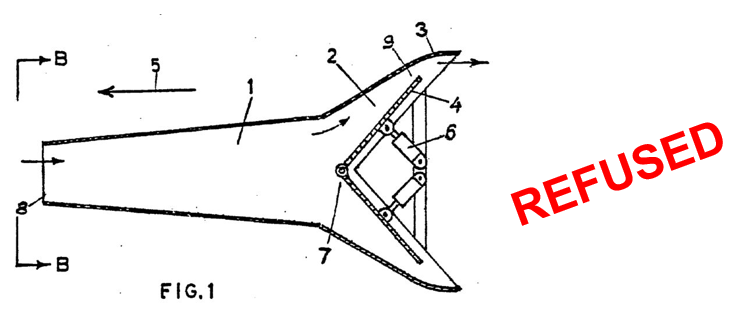

Occasionally, an applicant can suggest they are pushing too hard on the boundaries of established physics for their application to be sufficient. We must express extreme caution in presenting what may be a technical advance in such a way: there is a long line of cases where such matters are rejected. A typical example is Bolesta’s application, T0883/90, in which the applicant freely admitted in the description that:

“… according to the at present prevailing view, the existence of the reactionless appearing force seems to disagree with the Third Law of Newton and also the conversion of molecular energy of the environmental fluids into work seems to disagree with the Second Law of Thermodynamics”.

With Claim 1 in the application starting as follows, the EPO Board of Appeal had no option but to issue a refusal:

“A propulsion apparatus for performing the linear propulsion characterized in that the propulsion is effected by RAF, being the abbreviation of "reactionless appearing force…”.

As the Board noted:

“it is not possible for the skilled person to understand the reactionless appearing force (RAF) explained in the description… It would not be possible for him to understand how the claimed continuous conversion of environmental energy into work which is contrary to the well-established Second Law of Thermodynamics, can be carried out”

(b) Insufficiency by Excessive Claim Breadth

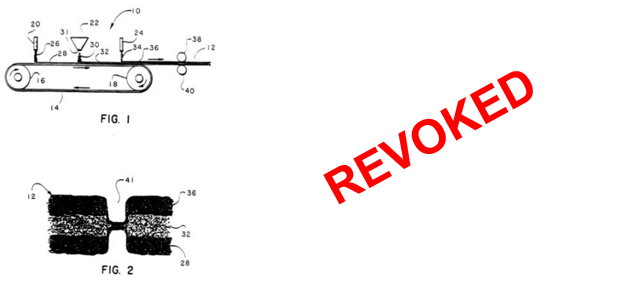

EP2338421 was filed by Quill Medical Inc. and relates to a suture for surgical use

In the description, the applicant provided a range of suitable shapes for the suture:

“… the sutures could also have a non-circular cross-sectional shape that could increase the surface area and facilitate the formation of the barbs. Other cross-sectional shapes may include, but are not limited to, oval, triangle, square, parallelepiped, trapezoid, rhomboid, pentagon, hexagon, cruciform; and the like.”

However, Claim 1 included the following:

“A barbed suture (S1...S4) for connecting human or animal tissue in …. comprises a plurality of barbs projecting from an elongated body having a first end and a second end and a diameter (SD1... SD4) of a circular or non-circular cross section in the range of from about 0.001 mm to about 1 mm, …”

None of the non-circular shapes of the examples have a diameter, and therefore this claim is insufficient.

During the Appeal proceedings, Claim 1 of the Main Request was found to be insufficient for excessive claim breadth (ITC v Quill T1064/15). The Appeal Board decided that the skilled person “does not know how to select the cross-section dimension of a non-circular suture in order to improve the [wound] closure strength … an essential part of the teaching of the patent in suit.”

The applicant filed an Auxiliary Request where Claim 1 was limited to a suture with a circular cross-section, and this was allowed.

(c) Insufficiency by Ambiguity

EP0700465 relates to a personal care article, comprising a nonwoven fabric laminate. The application was filed by Kimberley-Clark Worldwide.

The claim includes limitations on the cup crush peak load value and a cup crush energy value. When trying to ascertain what these values are, the skilled person would refer to the description. The description includes details of the test along with details of the cup crush testing machine, including the model number and manufacturer.

The patent was opposed by The Proctor & Gamble Company on a number of grounds. The Opposition Division decided that the invention was sufficiently disclosed. The opponent filed an appeal. The Appeal Board came to a different conclusion (T 0252/02) and agreed with the appellant’s statement that the test is not a standardised test and wasn’t sufficiently disclosed. Their arguments were centred around the fact that the shape of the cup and the base of the cup were not disclosed.

The Appeal Board stated: “Depending on the arbitrary choice… different geometrical forms are obtained (e.g. cylindrical, frustoconical, with rounded or flat top), with different amounts and arrangements of wrinkles and pleats in the walls of the cup ... Since these factors affect the strength of the cup, different results are obtained for a given fabric depending on the arbitrary choice made by the skilled person… the results of the cup crush test depend from arbitrary choices …and therefore the disclosure of the patent in suit is … insufficient.”

This is a classic example of what we call “shooting yourself in the foot”; as once a European patent has been granted with an insufficient feature in the independent claim(s), it cannot be removed as this would broaden the claim, which is not allowed after grant.

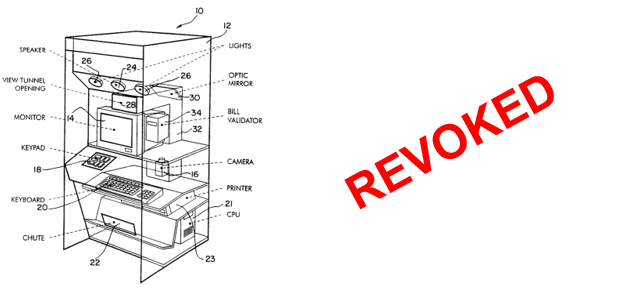

Our last example is GB2314719 and describes an interactive photo kiosk. This application was filed by American Photo Booths Inc. Revocation proceedings were filed after the patent granted. The Claimant (Eastman Kodak Company) sought revocation of the patent on the grounds of lack of novelty, industrial applicability and sufficiency.

In this case, the application contains a mistake. The Claimant submitted that Claim 1 and two paragraphs in the description do not make sense.

Claim 1 read: “A direct view photo kiosk for automatically taking, processing and delivering… photographic images of the user posed at the photo kiosk comprising: … within said kiosk to form a folded and extended length optical path to narrow the depth of field within said region provided for the user to pose; an electronic processor….”

The Claimant submitted that since it is not physically possible for an extended length, folded optical path to give rise to a narrowing of the depth of field and a consequential defocusing of the background image, the claimed invention cannot work. The Claimant stated that Claims 1 and 6 contained a mistake because increasing the distance between the camera lens and the subject will increase the depth of field, not decrease it. They filed evidence which supported their arguments.

The Claimant also submitted that since the invention cannot work, the application does not, and could not, disclose the invention clearly enough and completely enough for it to be performed by a skilled person. The Hearing Officer agreed, and the patent was revoked.

If this error had been spotted sooner, it may have been correctable prior to grant, but this would have been at the Examiner’s discretion (depending on whether it was considered obvious that an error had occurred).

Hopefully, these examples have raised some points to consider when you’re next drafting or reviewing a patent application for filing. The examples illustrate that even the finest engineering companies in the world with top-rate IP departments can make mistakes in their briefing disclosures. These errors can be small yet fatal.

Take home points:

-

Make sure you have complete understanding of an application you are responsible for filing.

-

If you spot an error, try and correct it prior to grant.

-

Be careful with tests and their parameters especially when they are being claimed.

-

Check that any terminology used in Claim 1 has been defined in the description.

-

Be extremely careful that in-house terminology means what the skilled person outside the company would understand.

-

Claim the product or process without claiming effects beyond the known laws of physics.

-

Try not to shoot yourself in the foot!

If you would like to know more, please get in touch with Jim Miller, Gail Taylor or your usual Kilburn & Strode advisor.