Interestingly, and indeed crucially as it turned out, neither registration covered class 16 (the class for printed goods including photos), nor included a description of the mark. Back in 2010, Polaroid had in fact applied to register a very similar EUTM in class 16 (plus classes 1 and 9), this time including a description of the mark as below. However, this was later withdrawn, presumably following an insuperable inherent grounds objection:

“The mark consists of the rectangular border area around the solid grey area. The solid grey area inside the rectangular border area does not form part of the mark.” - EUIPO description of EUTM 008873416.

Scarecrows or strawmen?

Fast-forward to 2018 and cancellation actions were filed against the two EUTM registrations by two unknown individuals, widely considered to be strawmen acting on behalf of Polaroid’s biggest competitor, Fujifilm.

Polaroid were most unhappy about this, raising concerns as to the “transparency” of the proceedings and arguing that the actions did not seek to protect the general interest and sound competition in the market, but were instead an attempt to deprive Fujifilm’s “most important competitor of its most characteristic and historical asset.”

We examine the detail of the two actions and decisions (which were identical) below, but it’s worth noting that right at the start of the decision(s), the Cancellation Division specifically addressed Polaroid’s complaint as a “preliminary remark”, giving short shrift to their concerns and noting they bore “no relevance to the present case” which was based on absolute grounds. They further noted that as long as the applicant for cancellation is “any legal or natural person with the capacity in his own name to sue and be sued”, it is irrelevant whether or not he’s collaborating with another entity.

A zoom in on the grounds

The applicants for cancellation threw the kitchen sink at Polaroid, relying on six grounds:

-

Article 7(1)(a): That the contested marks consisted of a simple geometric form, easily identified as an instant photo frame. The marks were not sufficiently specific to qualify as a trade mark.

-

Article 7(1)(b) and (c): That the marks were devoid of any distinctive character due to their very common and basic shape. The marks were not, therefore, able to perform the essential trade mark function – to distinguish one undertaking from that of another. In addition, the marks, when perceived as instant picture frames, would be descriptive of any of the photography-related goods and services (e.g. Class 9 cameras or Class 40 printing services).

-

Article 7(1)(d): Though pleaded, the applicants’ arguments that the marks had become customary in the established practices of the trade were interwoven with their arguments that the marks are a common design element used in the market by a number of players.

-

Article 7(1)(e): That the shape of the marks is determined by a technical necessity and, therefore, should be precluded from registration. To support this ground, the applicants provided a history of the technology behind instant photographs, filing in their evidence details of expired patents.

-

Article 59(1)(b): that Polaroid had filed the marks with ill intent, to prevent and obstruct competitors in the markets to use a common design element in their business activities (e.g. bad faith).

Despite the number of grounds pleaded, as is common in registry proceedings, the Cancellation Division did not analyse each ground and abruptly ended the decisions once they deemed the cases to be won or lost. An unfortunate system where parties are left asking “what if?” or “how close would I have been?”. Putting together a case, particularly such as this where significant evidence was filed, can be a time-consuming and often expensive process for a business. One would hope that if the parties went to the effort of putting forward their case, the Cancellation Division would follow suit (not least for the benefit of examining important points of law).

Interestingly, despite the strawmen arguing the marks were not even “signs” (the basic requirement for a trade mark application) under Art 7(1)(a), this ground was not even mentioned in the decisions. Instead, the Cancellation Division provided a helpful refresher on the registrability of geometric shapes.

In short, a low level of distinctiveness is fine, but you can’t have no distinctiveness at all. Signs which are excessively simple and consist of just a single basic geometrical figure (e.g. a circle, line) are not capable of conveying a message which consumers will be able to remember, hence they won’t be seen as a trade mark unless they have acquired distinctive character through use.

The same applies to two basic geometrical shapes (e.g. rectangles as here), not combined in an unusual or memorable way but merely placed within each other in the same orientation. The present marks also weren’t helped by the fact that commonplace labels and frames are often formed of similar shapes.

The marks also didn’t contain any additional elements to save them; the white colour and specific proportions didn’t add anything or cause consumers to pay attention or attribute trade mark origin to the marks.

As a result, the marks were found not to enjoy even a minimum degree of singularity and memorability and would not be perceived as a sign of origin.

Some of the Cancellation Division’s arguments were not backed up by evidence, which may perhaps lend subject matter to the appeals, but ultimately it seems hard to argue these marks have inherent registrability, even if some of the reasoning was flawed.

The decisions also provided a useful reminder about the weight given to precedents. Both parties had referred to previous EUTMs accepted (or not) to support their positions, but the Cancellation Division noted that precedents must be “genuinely comparable” to be persuasive. The interlocking triangles relied upon by Polaroid were held to differ “significantly” from the present marks; the optical illusion of two intertwined marks (which didn’t in fact exist) was a memorable and unusual feature which distinguishes it from the banal combination of basic geometric shapes. The strawmen’s precedents, on the other hand, were found to be “very much analogous” to the present case and hence far more compelling.

The Cancellation Division further noted that if a mark falls foul of Art. 7(1)(b), the Division can’t decide otherwise simply because an equally non-distinctive mark has been registered in the past. In other words, two wrongs don’t make a right.

Lastly, it made a slightly cryptic comment, apparently undermining the quality of its examiners, noting that comparable precedents should concern cases “where the Office took a reasoned decision”, rather than trade marks accepted by departments “which lack any apparent motivation in their findings” as to the accepted distinctive character or otherwise of a mark. This would suggest that only decisions from the Board of Appeal and upwards will be considered persuasive, not the state of the register per se.

Shooting yourself in the foot…

The decisions also picked up on a rather unfortunate comment by Polaroid, who were perhaps anticipating a failure on inherent registrability. After admitting the marks were “a rather simple geometric form”, Polaroid went on to argue that this was not a reason to consider them non-distinctive, because the public “associate them with Polaroid”. As the Cancellation Division noted, this would, in fact, rather suggest that the signs had acquired distinctive character through use, not because of their inherent distinctiveness.

Polaroid filed significant evidence to support their claim that the marks had acquired distinctiveness through use in the EU. The evidence itself was nothing out of the ordinary and included a range of documents, including product images, sales figures, license agreements and surveys. However, serious questions were asked of the value of the evidence and Polaroid failed to provide adequate answers.

The first question was whether the evidence showed use of the marks as registered. To recap, the marks as registered are images of two rectangles, a smaller one within the other. Many of the examples provided by Polaroid were of photographs framed within a white border (e.g. of the mark but containing pictures within the inner rectangle.) The Cancellation Division confirmed that this was not use of the marks as registered and is a cautious reminder to be clear and specific about the protection you are seeking when registering.

The second question was whether the evidence showed use of the marks in relation to the goods and services registered. Amongst the evidence were pictures of product packaging on Class 9 goods, some references to sales for Class 25 goods and a ream of documents showing instant photographs. Whilst acknowledging that some of the evidence pointed to use of the marks as registered for Class 9 goods, the Cancellation Division noted that the use on the back of the packaging, alongside other technical information relating to the product, might not be perceived by consumers as being indicative of origin. Rather, consumers might see the mark as indicating the format of the pictures that the Class 9 goods produce. This was despite Polaroid’s efforts to state on the packaging, alongside the marks, the following notice:

“Instantly recognizable. Instantly reassuring. The Polaroid Classic Border and Polaroid Color Spectrum logo let you know you’ve purchased a product that exemplifies the best qualities of our brand and that contribute to our rich heritage of quality and innovation.”

As to the sales figures for Class 25 goods, the Cancellation Division did not consider the evidence to be particularly probative, given the unknown source of the information and the “not overwhelming” numbers.

What made the battle hard for Polaroid was, crucially, that their registrations did not cover Class 16 goods. The evidence submitted showing the marks used as instant photographs, which is arguably their core use, was unhelpful.

Surveys without the right focus

Polaroid carried out two surveys to evidence that consumers had come to identify the marks as being indicative of Polaroid’s brand.

The first survey, carried out in 2015, covered the UK, France, Germany and Spain. Following Brexit, the perception of the UK public became redundant. The focus was then on the remaining territories and the Cancellation Division deemed the scope to be too narrow for the results to be extrapolated to the remaining 24 Member States.

The second survey, carried out in 2019, covered a wider range of territories, adding to the first survey Denmark, Italy, the Czech Republic, Poland, Belgium and the Netherlands. Again, the Cancellation Division was critical of the scope. The survey covered only a third of all Member States and crucially ignored certain markets. In this instance, the Cancellation Division noted the absence of any consumer respondents hailing from the Balkan Member States.

What killed the value of both surveys, however, were the leading questions:

-

Q1: In the world of photography, what brands do you know in the following list? (several brands are listed, Polaroid among them)

-

Q2: Personally, would you say that you know the brand Polaroid (very well, quite well, in name only, not at all)?

-

Q3: To what commercial origin/brand do you associate this form? Only one possible answer. (the contested marks were shown)

-

Q4: Quickly look at these different signs. Do you recognise the picture which we showed you earlier? Only one answer.

|

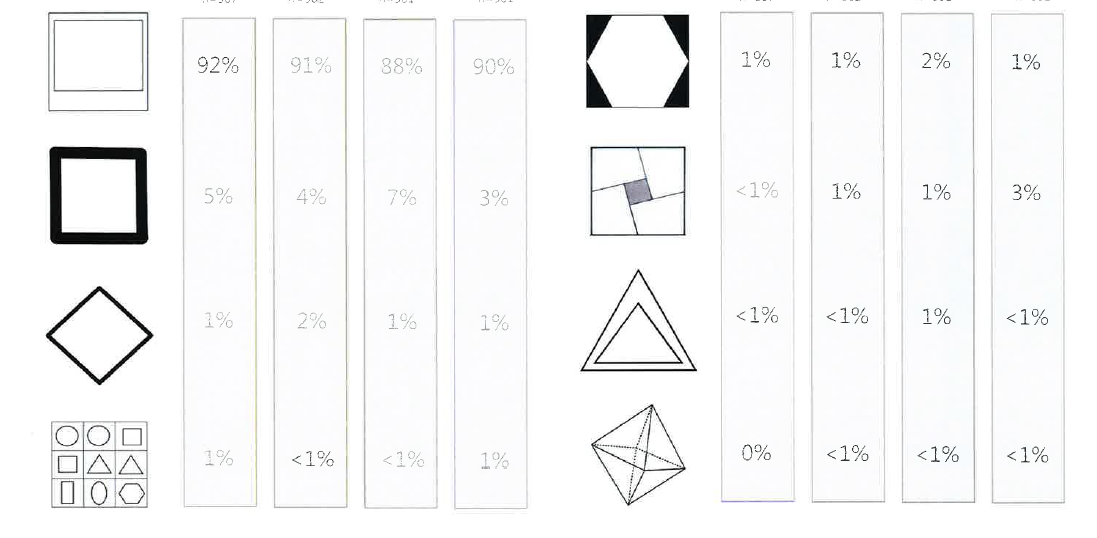

The second question puts the Polaroid brand firmly in the minds of the respondents, irrespective of how they might have answered the first question. This then leads to the third question, where only one answer was possible. Even if the respondents were to consider the marks to come from a number of brands that might use instant photography, or that they might not even consider the marks to be trade marks, they are forced to associate the marks with only one company. The last question was also held to be of low value, as none of the other shapes represented included a combination of two rectangles. The Cancellation Division stated, “It is not surprising that the participants of the survey are able to recognise a rectangle from a triangle or a completely different shape altogether, but this says absolutely nothing about whether or not they think that the contested sign is a trade mark”.

When taken as a whole, the evidence provided by Polaroid was found to be lacking in key areas and was not sufficient to support their claim of acquired distinctiveness. Accordingly, the Cancellation Division upheld the actions in their entirety and the marks were invalidated.

An appealing picture?

In late 2021, Polaroid appealed the decisions to the Board of Appeal, arguing that the Cancellation Division’s finding of non-distinctiveness was incorrect and lacked factual grounding. They requested that the decisions be annulled and the cases be returned to the Cancellation Division for further prosecution. They also requested that the additional grounds not decided at first instance be revisited. Not surprisingly, the strawmen requested in early 2022 that the appeals be dismissed and, a few months later, Polaroid withdrew their claim of acquired distinctiveness. The marks were then transferred to Polaroid IP B.V.

The appeal decisions issued in late June 2022, with the Fourth Board of Appeal finding heavily in the strawmen’s favour. The Board agreed with the Cancellation Division that in both cases, “The sign is so simple that it lacked distinctiveness for all its goods and services”. Perhaps in an attempt to discourage a further appeal, the Board also took great pains to explain why the other marks relied upon by Polaroid were not comparable.

So perhaps this time Polaroid really have run out of any ink-lination to take this further. We shall watch this space!

Practice points

The cancellation decisions raise a number of learnings regarding the distinctiveness of device marks. Our key takeaways are below:

-

Be clear (both in your own mind and in the application – using a description if need be) what your mark consists of, especially if it’s a less common device or positional mark;

-

Be clear what about classes you need protection for and file accordingly;

-

Consider national applications (cf an EUTM), especially if you anticipate an uphill struggle to prove acquired distinctiveness (either to secure registration in the first place or in a later third party challenge);

-

Be careful how you present your arguments – don’t undermine yourself!

-

Even trade mark notices might not portray the intended ‘brand origin’ message in certain contexts – make sure the legal and marketing people work closely together;

-

Surveys can be time-consuming and expensive evidence-gathering exercises – make sure the questions and scope are carefully considered and, above all else, avoid leading questions!

-

Remember that anyone can file a cancellation action against an EUTM on inherent registrability grounds – by contrast with some other jurisdictions where one must have a specific interest or legal standing to challenge a third-party mark (e.g. if the earlier mark is blocking your application or if you’re facing infringement proceedings based on the mark in question).

Get in touch

For more information about securing UK or European trade mark protection, or if you would like any further advice on any IP matters, please contact Rowena Tolley or your usual Kilburn & Strode trade mark adviser.